Examine, a free weekly newsletter covering science with a sceptical, evidence-based eye, is sent every Tuesday. You’re reading an excerpt – sign up to get the whole newsletter in your inbox.

Regular readers might remember the problem I devoted a column to trying to solve late last year: why was I so ravenously hungry by 6pm? Could a 3pm chocolate be to blame?

I concluded it probably was, causing a surge in my blood sugar and then sending it nosediving until my brain demanded calories.

That was a guess at my glucose metabolism. Technology now promises to make it possible to know. Many companies will sell you a continuous glucose monitor – a tiny needle-patch that samples your blood sugar every five minutes and transmits data to your phone via Bluetooth.

The monitors are most typically used by diabetics, but more and more wellness companies, such as Vively (which supplied mine) are promoting them as a way of seeing how your body responds to different foods. It’s worth saying here: the general population do not need to use these devices unless recommended by their health professional.

I wore it for two weeks, and then took the data to several blood sugar researchers. Here’s what I learnt.

Think about the body as having short (glucose), medium (glycogen) and long-term (fat) energy storage.

When digested, carbohydrates in your food (think oats, bread, fruit, vegetables) produce glucose, your front-line fuel. As glucose enters the blood, the hormone insulin is released in response, which triggers cells to absorb the glucose.

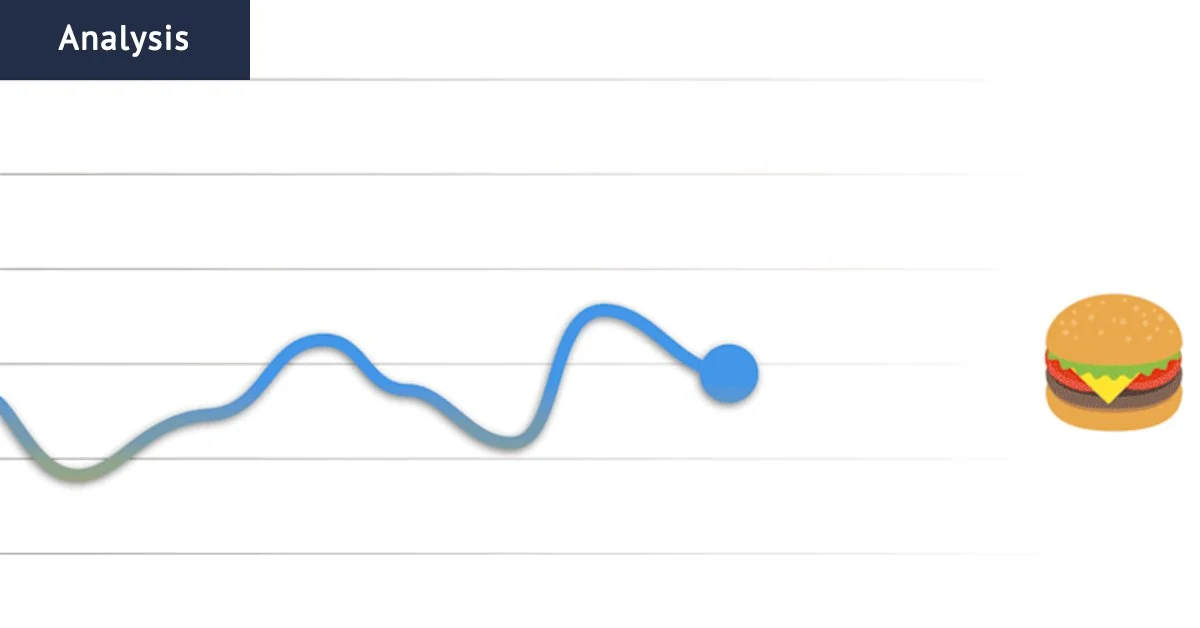

You can see that clearly in my monitor’s data: I eat, my blood glucose rises, insulin rises, and it is quickly cleared.

The muesli, fruit and coffee I had for breakfast produced quite a large increase in my blood glucose. That’s simply because the meal was high in carbohydrates – not because it was unhealthy.

“People may think they need a flat line. Physiologically, you eat a meal that may be perfectly balanced and contains everything you need, your blood glucose level will rise,” says Dr Brooke Devlin, a lecturer in nutrition and dietetics at the University of Queensland. “That’s normal, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

How quickly blood glucose rises is governed by how many carbohydrates were in the meal, how complex they are (simple: bread; complex: vegetables), whether they are liquid or solid, and how much protein, fat and fibre were in the meal; all three macronutrients slow digestion.

Now look at the pre-breakfast hours, when I was sleeping. My glucose is steady. Why? When we eat, our bodies store excess glucose in the liver as glycogen (about 12 to 24 hours’ worth of fuel). This medium-term energy is slowly released overnight to keep blood sugar level.

Processed food really knocks around my blood sugar

On January 27, I was on the road to cover the Otways bushfires. Around midday, we pulled over at a servo and I tried to pick a healthy option … three multigrain sandwiches with tomatoes, egg and ham, and an iced latte (no sugar).

That meal sent my blood sugar on a rollercoaster: three sharp peaks followed by deep valleys.

Then, worrying the sandwiches wouldn’t be enough to keep me full, I went for a chocolate-coated protein bar and another iced coffee in the afternoon.

My blood sugar rose and then fell and fell, down to my lowest reading for the day. At this point, I wrote a note: “ravenously hungry”.

On January 28, I fell for the same trap, selecting a chicken and salad roll for lunch. Seems healthy? I got my highest blood sugar reading for the fortnight, followed by a crash. Again I wrote down “extremely hungry”.

“The mayonnaise probably has sugar in it. As consumers, we don’t always understand what’s in the processed foods we buy,” says Professor Gary Wittert, a leading obesity and appetite researcher at Adelaide University. “You don’t know how much sugar is in the roll or the mayo. You think it’s healthy.”

Do blood sugar spikes matter? I got different answers. Wittert thinks it’s best to minimise spikes from refined carbs as they are pro-inflammatory.

Associate Professor Neale Cohen, director of clinical services at the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, is more sceptical. “We don’t like seeing levels that are extremely high, because we think they cause damage. But damage from diabetes (characterised by high glucose levels) is done over months and years. In the short-term there is minimal damage.”

A big night

January 23 was my best day of glucose control. I ate every three hours, going for a chicken curry with potatoes, a chicken salad with noodles, and a couple of protein yoghurts. “Your meals had more of a protein focus and less of a high simple-carb focus,” says Hailey Donnelly, a diabetes dietitian at the University of Newcastle.

And I hit the gym the day before. Our bodies are more sensitive to insulin in the 24 hours after exercise, meaning glucose is absorbed more quickly.

You’ll notice my glucose control is a lot tighter in the morning than at night. That’s normal for healthy people: insulin sensitivity is highest in the morning and falls throughout the day.

That night, I went out dancing far too late, and spent the next day feeling very sore in the head. And my graph was much more spiky all day.

Wittert tells me about running a similar experiment in 2012, deliberately sleep-depriving healthy adults and then monitoring their blood sugar. “After four days of that, they were waking with blood sugars like you. Sleep restriction causes insulin resistance,” he says.

It’s not just sleep. Stress triggers the release of cortisol and adrenaline, which leads to an increase in blood sugar. I saw this when I was giving a talk to a group of science journalists; my sugar raced upwards. Too much stress long-term can drive insulin resistance.

The chocolate experiment

Finally, I wanted to test out my hypothesis: would a 3pm chocolate bar mess with my blood glucose and leave me hungry?

The graph jumps up – not too sharply, as about half a KitKat’s energy comes from fat – and then falls sharply. I ended up with a blood glucose level lower than before I ate the high-sugar snack. And I was hungry.

This, to me, looks like strong support for the sugar-crash hypothesis. But the researchers I put this to are less convinced.

“There are these stories that go around that spike causes hunger. I don’t think there have ever really been studies that show this,” says Cohen. “It’s a very complicated thing, there’s a whole lot of hormones in the gut and the brain that control hunger. Hunger is not a simple sugar-related response at all.”

How much does the data matter?

I personally found the data fascinating, although I’m less convinced it is useful. I already know I should eat less junk food. Vively’s dietitian, Holly Morrison-McBain, tells me I seem to be quite sensitive to carbohydrates and could try reducing how many I eat in the evening, potentially improving my sleep. She and Wittert both argue too much glucose variability is harmful in the long term.

Other researchers I took it to are more sceptical, though several admitted to using the devices themselves.

Part of the problem is the sensor’s accuracy. Cohen suspects there’s likely a large margin for error. And who is most likely to be able to pay $300 for a blood glucose tracker? The worried wealthy are not the people who really need them.

Add that into the questions around whether sugar spikes actually matter, and Cohen says he “hasn’t seen anything so far that really makes me think this is a useful thing to be measuring continuously”.

Vively supplied a continuous glucose monitor for review for two weeks.

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.