Growing new heart cells is the holy grail for cardiologists. Textbooks say it can’t be done.

But in a tank of liquid nitrogen, frozen in time for 18 years, one rare heart has provided the first evidence that human hearts try to repair themselves after a heart attack.

A University of Sydney-led research team hopes their discovery may lead to therapies that turbocharge this natural process to reverse heart failure.

For decades, scientists have known some animals can regenerate heart muscle cells, called cardiomyocytes, after a heart attack. A zebrafish can completely regrow its heart, and mouse models show an increase in cardiomyocytes dividing and multiplying – a process called mitosis – in the tissue surrounding the heart attack-affected area.

“But that had never been shown in humans,” said Dr Rob Hume, a University of Sydney research fellow and lead of translational research at the Baird Institute.

Sean Lal, a cardiologist and professor of clinical and molecular cardiology at the university, said medical students were taught that humans can’t grow new heart cells; “that the number of cardiomyocytes you are born with is effectively the amount you die with unless they’re killed off after a heart attack.”

To disprove this, replicating the animal models in humans – inducing a heart attack, then analysing the tissue – was out of the question. But in a moment of serendipity, Lal stumbled upon a fluke-of-a-heart while taking inventory at the Sydney Heart Bank: an organ that satisfied near-impossible criteria.

A one-of-a-kind heart

The heart belonged to a 48-year-old man who suffered a catastrophic heart attack almost two decades ago. The man was brain-dead and on life support. He was an organ donor, but his damaged heart could not be given to someone else, and his next of kin consented to donate it for research.

His heart was quickly harvested before life support was withdrawn. It was then cut into small fragments, snap frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen.

“Essentially, the tissue and cells were ‘frozen in time’,” Hume said.

“I thought, wow,” said Lal of the moment he found the heart in the bank. “This is the closest thing we could get to those rodent models. It was our best chance to ever show this in humans.”

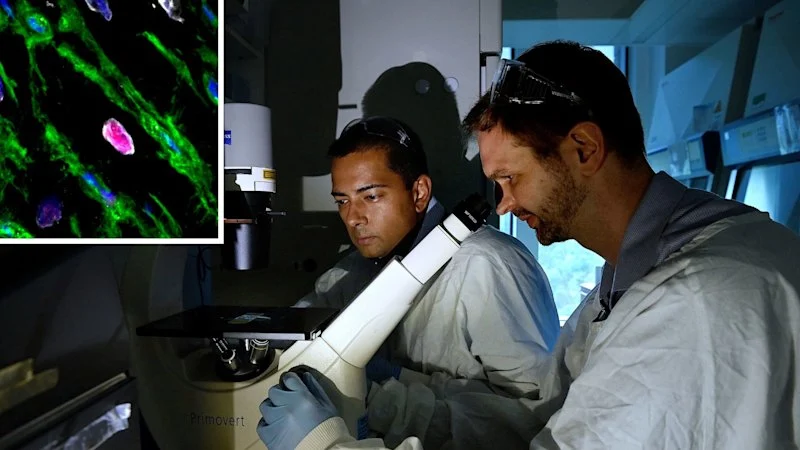

The research team conducted a detailed investigation of the tissue using advanced techniques across immunohistochemistry, proteomics – studying proteins – and RNA analysis.

About 11 per cent of cardiomyocytes in the heart tissue samples taken from around the area affected by the heart attack showed signs of mitosis, Lal said.

“When you do the microscopy on a slice of that tissue, you can see those cardiomyocytes actually splitting,” Hume said.

Dr Robert Hume

But this was just one heart, and the chances of finding another like it were almost non-existent.

To build on their findings, the researchers are collecting tissue samples from patients undergoing bypass surgery at RPA who have suffered heart attacks seven to 10 days earlier. So far, mitosis has been seen in 7 to 8 per cent of cardiomyocytes in these samples, Lal said.

To repair a heart would require 25 to 50 per cent, Lal said. “But that this is naturally happening is really exciting. Can we tap into this to make even more new heart cells?”

Why is this happening?

Lal suspects hypoxia – the oxygen deprivation that kills heart tissue downstream of the heart attack blockage (including cardiomyocytes), also triggers this regenerative phenomenon in cardiomyocytes around the edges of this dead tissue.

This hypothesis struck him years earlier while studying fetal human hearts.

“Fetal hearts make tonnes of new heart cells in utero, which is an oxygen-low environment,” Lal said.

“Then it’s switched off when we’re born, and effectively by the age of five to 10 years old, we don’t make any more.

“It’s almost like the heart has some inbuilt memory. Maybe when you have low oxygen after a heart attack, you reprogram your heart cells to make new cells like you did when you were in utero. That is what we are exploring.”

Their analysis found genes that are switched on in utero to make new heart cells were activated only in the area around the heart attack.

Monash Victorian Heart Institute director Professor Steve Nicholls said the finding was a very significant, though small, step on a long path towards potentially enhancing this phenomenon with treatments.

“The holy grail really has been: is it possible to regenerate heart muscle?” Nicholls said.

“They definitely see mitosis. It’s not a lot, but there is potential there and, I think, gives us all hope.

“And if we can do that, well, that would make a massive difference for people who suffer extensive heart damage with a heart attack.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.